Arts & Culture

A new book—and a new oral history project—highlight the rural women whose stories continue to shape Appalachia

March 8, 2023

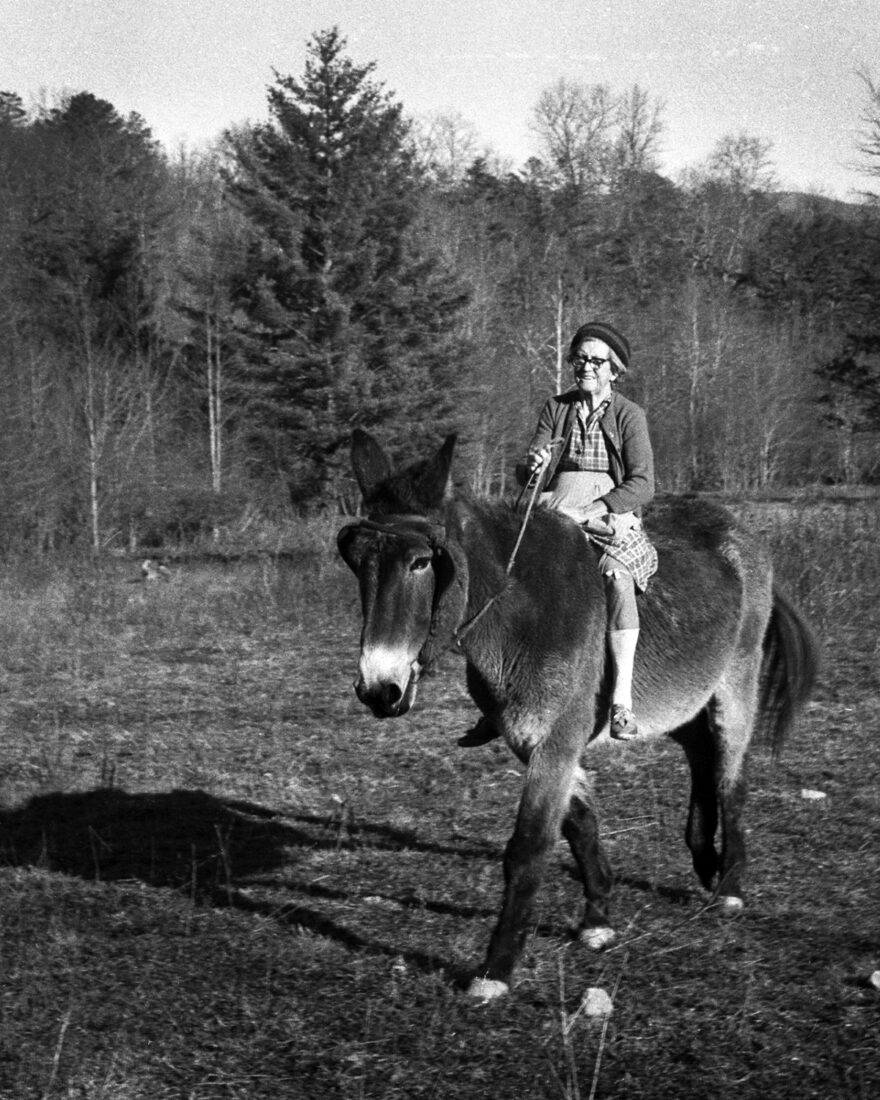

photo: Courtesy of FOxfire

Maude Shope riding her mule Frank bareback, 1971.

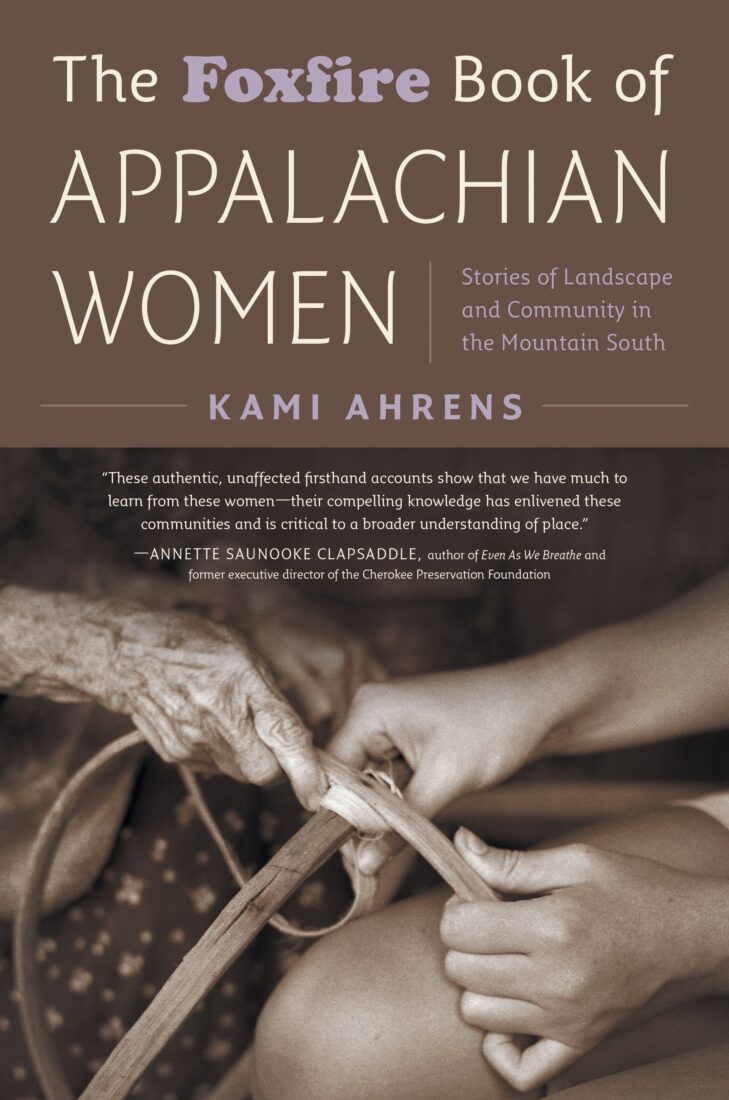

Founded in the late 1960s by a high school English teacher to defy the stigmas and disparaging portrayals of rural Appalachia, Foxfire magazine has, for more than fifty years, empowered rural Southerners to tell their own stories. Students armed with notebooks, cameras, and tape recorders interview family members, area elders, and community leaders to paint a fuller, more authentic portrait of the region—a practice that continues today in Foxfire’s home of Rabun County, Georgia. Released this month, the new book The Foxfire Book of Appalachian Women: Stories of Landscape and Community in the Mountain South pulls from more than five decades of oral histories to highlight some of the strong-willed and inspirational women who call Appalachia home.

Early interviews in the book detail the struggle and resourcefulness of mountain living—working for dime and quarter wages, bartering with crops and home-canned food, and relying on your neighbors—and how folks maintained a strong sense of pride through it all. Ethel Lamb Corn described being the “oddball” for her handmade dresses; “I didn’t want nothin’ made like nobody else’s,” she said during her 1971 interview, “but I liked my things different. I guess I’ve been talked about a’plenty, but I don’t care.” Maude Conley Shope never learned to drive, even as cars became more commonplace; she rode her mule to get wherever she needed. “Used to ride him to Otto [North Carolina] to get groceries,” she explained in her own 1971 interview, adding, “Yes, sir. He’s something.”

Maude Shope stepping out of her home, 1971.

Histories from Black women, including Beulah Perry, Anna Tutt, Carrie McDonell Stewart, and Lena Dorsey, touch on the realities of living in the Jim Crow South— like segregated dining and dances—and the limited career opportunities available to them. In her 1977 interview, Stewart described how Black people were forced to eat in a restaurant’s kitchen after white patrons finished their meals in the formal dining rooms. “It was just a rule, no matter what or how,” she said. “I don’t know why they wanted it to be that way, but they did, because I remember that very well.” Tutt remarked that “a lot of people look back with hurt, but I don’t want to do that.” Reflecting years later, one of Foxfire’s white students admits in the pages that she “ran into some dead ends” from “people who just didn’t want to talk about the things they felt might offend me, problems between Blacks and Whites.”

Beulah Perry demonstrates how to weave a white oak cotton hamper to Foxfire students Mary Garth (left), Butch Darnell (center), and Mike Cook (right), 1970.

More recent oral histories include the influential Cherokee potter Amanda Sequoyah Swimmer, the faith healer and self-described “granny witch” Ronda Reno, and Sandra Macias Glichowski, an Ecuadorian immigrant who owns Blue Ridge Toys in downtown Clayton, Georgia. Glichowski moved to the area with her husband and two children in 2017 and quickly realized they “needed to open something in order to survive.” Her toy store carries products geared toward learning, ones that her kids help her pick out. It’s become a Main Street haven for children and for Glichowski. “The whole toy store’s been an experience to communicate and connect locally,” she says.

Ethel Lamb Corn holding a mess of sochan.

Foxfire is also kicking off a crowdsourced oral history project with the release of this collection, building on the contemporary interviews included. Women from or living in Appalachia can submit their written stories or voice recordings via Foxfire’s website; their chronicles will be a permanent part of Foxfire’s archives and could possibly be featured on the It Still Lives podcast or in the pages of the landmark magazine.

The Foxfire Book of Appalachian Women is captivating, resisting nostalgia with its authentic, honest, and sometimes contradictory experiences from women all over the region. For Kami Ahrens, Foxfire’s curator, director of education, and collection editor, this book charts a way forward during polarizing times. “Listening and learning from these stories,” Ahrens says, “and sharing our own experiences can help bring us together and build more resilient communities.” After reading through these histories, it’s clear that swapping stories together isn’t a bad way to get started.