Music

The country star reopens Ellis Theater, the first wing of his Congress of Country Music, as a way to revitalize his hometown

By Jim Beaugez

December 19, 2022

Ever since country star Marty Stuart left his home of Philadelphia, Mississippi, in 1972 to join bluegrass pioneer Lester Flatt’s band, he’s been trying to get back. It took three decades and the help of the late icon B.B. King, but he finally figured it out.

After King invited Stuart to visit his museum when it opened in Indianola in the mid-aughts, Stuart spent the drive back to Nashville deep in thought. “It was almost like that Blues Brothers thing—I’m on a mission from God,” Stuart says, seated backstage at the newly renovated, circa-1926 Ellis Theater in Philadelphia, about an hour south of Starkville. That mission, he says, was to cement his hometown’s place as a spiritual home of country music.

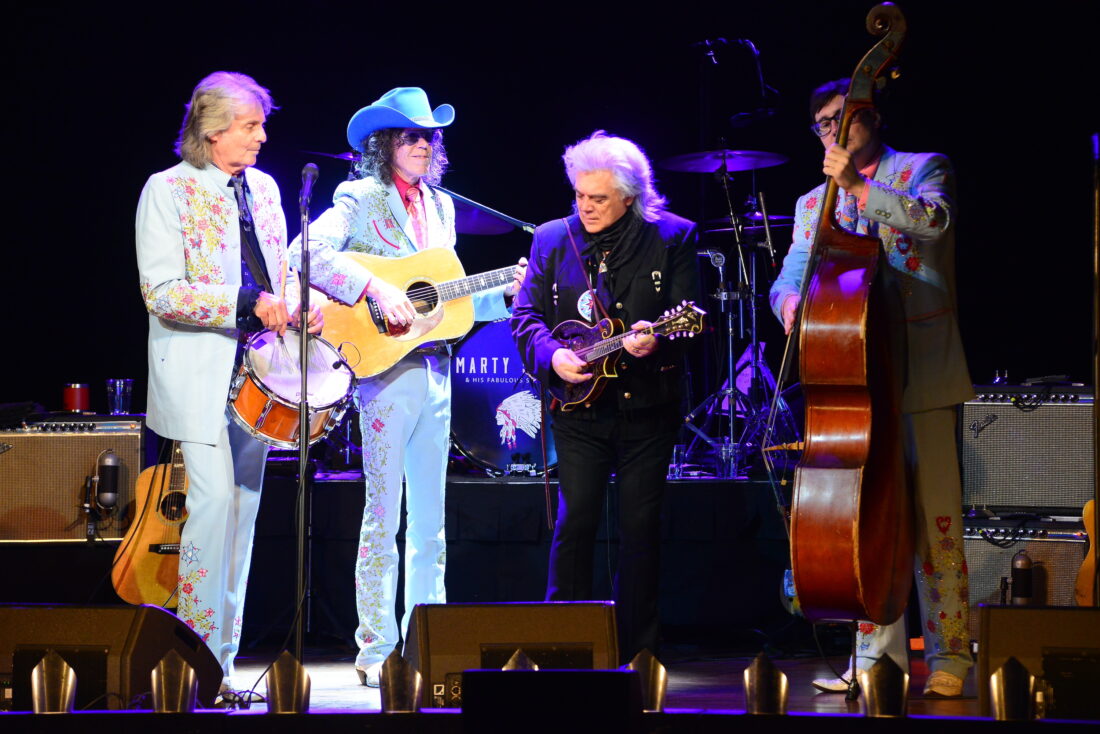

On December 8, Stuart turned fifteen years of planning into reality by reopening the five-hundred-seat movie theater he attended as a kid as the first wing of his ambitious Congress of Country Music project. He christened the auditorium, which will host a wide array of bluegrass and country shows, with a rousing performance that included appearances by his wife, singer Connie Smith, and bluesman Jontavious Willis. When the museum portion opens in 2024, visitors will get to experience country music history from the perspective of a fan—which Stuart certainly is, albeit one who has happened to acquire more than twenty thousand country music artifacts, often from the artists themselves.

“The first piece I bought was Patsy Cline’s train case at a junk store in Nashville for seventy-five bucks,” Stuart says. “When I started making more than two dollars at a time, I was advised to buy stocks and bonds, but buying George Jones’s guitar for three dollars when it’s worth ten [made more sense to me]. So, it just seemed like a rescue initiative, which was the right thing to do.”

After $4 million in renovations, the Ellis Theater now boasts a modern sound system and seats that were once used in the Kennedy Center. Vintage posters and photographs of country music’s golden era line the halls, while a hand-painted fleur-de-lis motif adds contrast to the theater’s midnight blue walls. At center stage, a wooden circle represents the legacy of the Grand Ole Opry, this one made with wood taken from the Ryman Auditorium; the hat shop in Bristol, Tennessee, where Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family recorded; and Herzog Studio in Cincinnati, where Hank Williams frequented and where Flatt and Earl Scruggs laid down “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.”

Before Stuart and His Fabulous Superlatives kicked off their opening-night performance, a group of Bogue Chitto Social Dancers from the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians performed a ceremonial routine.

“The thing that’s most important to me is that we’re a tri-racial community—Black, white, Native American—and if we opened with just a country music show, without acknowledging the community, it would be a hollow victory,” says Stuart, who is part Choctaw. “It’s important to me that people of every race come and just understand it. This is a spiritual home of country music, and you can drop all that other stuff at the door. It’s about love here.”

We sat down with Stuart to talk about his hometown Ellis Theater, the Congress of Country Music, and the artifacts that found him.

Marty Stuart and His Fabulous Superlatives on stage at the Ellis Theater’s opening night.

Why did you decide to invest in your hometown?

I left here on Labor Day in 1972 to go to Nashville for the weekend and ride along with my buddy who played with Lester Flatt, and at the end of the two days, Lester offered me a job. I didn’t leave here because I was mad; I didn’t leave here ’cause I wanted to go look for anything. But when I left here, I took this place with me. In the best of times and the worst of times, Philadelphia’s where I come home. Nashville’s where I live, but this is truly home.

What made the Ellis Theater important to your mission of preserving country music history?

I saw Elvis movies here. I saw The Sound of Music here. I saw John Wayne cowboy movies here. There was a Johnny Cash documentary called The Man, His World, His Music and we came here on a Sunday afternoon to see it. There was a scene in that documentary where he was walking through the woods with his gun and he saw a crow. He didn’t kill him, [but] he nicked him on purpose, and he picked him up. As John’s walking through the woods it’s biting his finger, and he’s singing “old Mr. Crow, da da da da da.” When I first went to work with John, I said, “You know, one of my favorite songs of yours is ‘Old Mr. Crow.’” He said, “You’re the only person that’s ever told me that.” I said, “I saw it at my hometown movie theater” [laughs].

George Jones’s Martin D-45 guitar in the theater’s lobby.

What’s the signature artifact in the Congress of Country Music collection?

That’s a hard one. Johnny Cash’s first black suit, Hank Williams’s lyrics, boots Patsy Cline was wearing when she lost her life. I can tell you this: the theme song here is “Orange Blossom Special,” that old fiddle tune, and the patron saint of music here is Ervin Rouse, who wrote it. Ervin’s fiddle, I would say, is probably the heart and soul of the artifacts.

Are you still on the hunt today?

Every now and then something comes along that gets me, but most of the things come find me. One of Jimmie Rodgers’s guitars, fully documented, walked up to me four years ago and I had to go cut yards for two weeks to pay for that one [laughs]. But how do you not pick up things like that?