On the road leading to a crematorium in China’s southern city of Nanjing where thick black smoke was billowing into the sky, the line of cars was so long that it wasn’t clear where it ended.

On the curb squatted a woman wearing a white mourning hat with her face buried in her hands, her cries piercing the air.

“It’s the new year,” she said in a video that first circulated on Chinese social media in early January. But “all kinds of cars are coming to collect dead bodies.” Because of the long queues, the corpses can stay in the car for up to two days, she said.

The harsh conditions under China’s COVID tsunami that the woman alluded to align with data from internal documents from Chinese authorities The Epoch Times obtained from multiple parts of the country in recent weeks. These details, together with interviews with local residents, paint a somber picture of the virus toll that contrasts starkly with the positive tone authorities have strived to project.

An analysis of dozens of files on daily cremation data from Nanjing, the capital of eastern China’s Jiangsu Province and home to about 9.3 million, shows that the city’s death figures shot up in late December, growing to as high as 761 in early January—nearly six times the average daily deaths in the city for the first five months of 2022.

The workload at the city’s seven operating crematoriums indicated the same trend. From Dec. 29 through Jan. 18, the latest Nanjing Funeral Management Office data available from the trove, the number of bodies processed ranged from about 300 to 774 a day, up to six times the roughly 130 bodies processed per day in the same period last year.

The data showed that the city saw a total of 8,233 deaths from Dec. 18 to Jan. 2, about four times the average 15-day death toll of 2,100 from before the latest COVID wave.

The official documents placed a heightened emphasis on secrecy. While cremation data is reported daily to city-level authorities, such data appears strictly off-limits from being released to the public.

“Report relevant information, data, and charts through emails, do not discuss them on QQ and WeChat,” stated a Jan. 11 document that summarized “key cities’ cremation service situation.” Both QQ and WeChat are dominant social media channels in China under the Shenzhen-based Tencent brand.

“Step up education on secret-guarding work. Strengthen secret-guarding and safety education of cremation industry workers,” it added. “Do not casually release cremation-related data and information.”

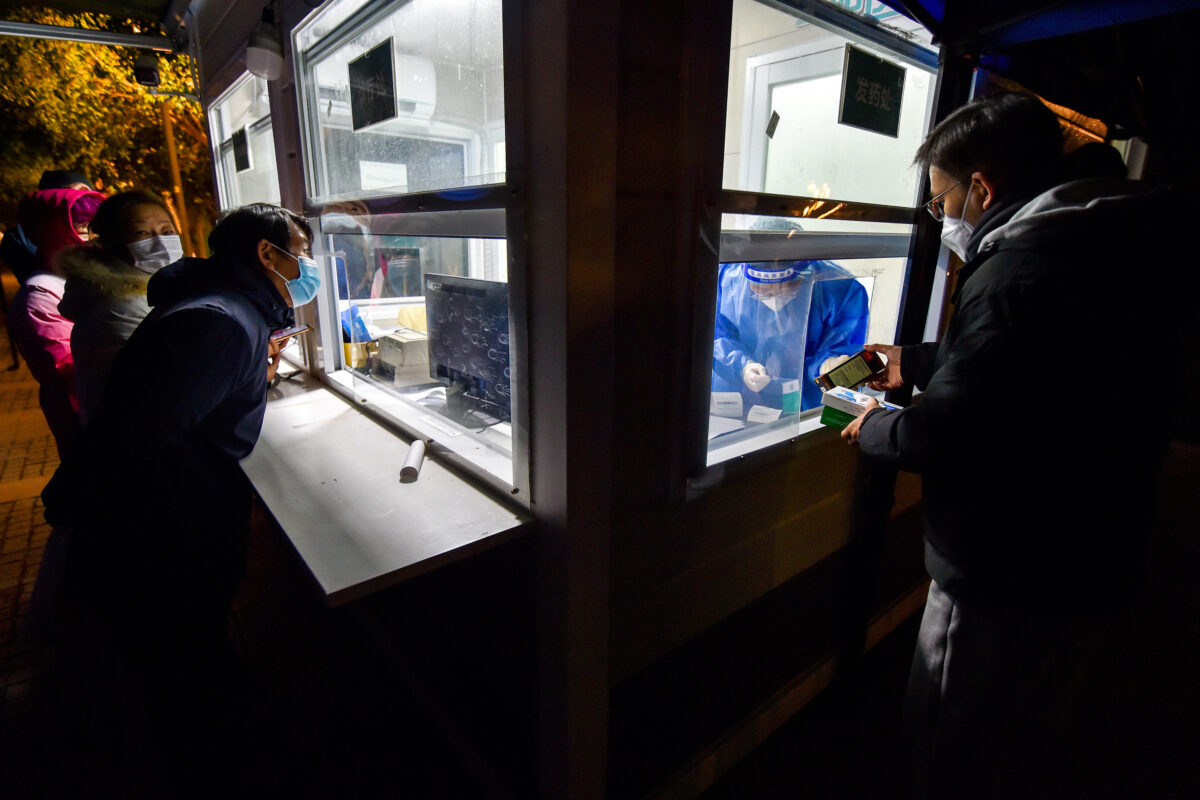

The same document indicated that a special panel had been set up chaired by the Nanjing Civil Affairs Bureau director to oversee the handling of bodies, and every cremation provider in the city was working 24 hours a day.

In the less than two-week span from Dec. 22, four funeral homes expanded their capacity by buying morgue refrigerators or requesting more manpower, the document stated. The largest purchase came from Lishui Funeral House for 120 refrigerators. Nanjing Funeral House, meanwhile, got 16 more hearses and 38 drivers.

The total number of additional staff for funeral services was 389 people as of Jan. 11, after 105 people were added eight days earlier.

Death Causes

Despite a significant surge in deaths, few of those cremated were marked as having died from COVID. From Nov. 11 to Dec. 17, the city cremated a total of 4,300 bodies—up by a third from the 3,070 three-year average from 2019 through 2021, the document stated.

Only 20 of those deaths were marked as COVID-related. Data from individual funeral parlors from that period further showed that all but one marked the bodies they handled as regular deaths.

Such practice is in line with Beijing’s widely-criticized policy that a death can be attributed to COVID only if it results directly from respiratory failure or pneumonia due to the virus. In addition, doctors have said that they’re been ordered not to list COVID as a cause of death in death certificates.

To date, Beijing has only registered less than 80,000 in-hospital COVID deaths. But experts say the figure is a vast undercount of the true death toll, pointing to the regime’s practice of hiding negative information and widespread accounts of overwhelmed crematoriums and hospitals.

A Nanjing resident surnamed Zhang, whose full name has been withheld for her safety, said that more than 20 seniors died in a neighborhood where she used to live.

Her neighbor noted the empty sofa and chairs at the compound’s entrance where seniors used to sunbathe.

“Those people are all gone,” Zhang said.

Her friend from the northern megacity of Tianjin recently lost his brother, who is around the age of 66. The man’s body stayed in a mortuary cooler for days until they bribed a local crematorium with gifts to get them to collect the body.

Another local, a woman surnamed Su, has a relative in Beijing, who managed to skip the more than two-month-long line at the funeral parlor by pulling strings to cremate his parent. But they still ended up waiting for days.

“There’s no question a lot of old people died. This is a fact,” Su, who declined to provide her full name for fear of reprisals, told The Epoch Times.

“But as to the actual COVID situation, we can’t tell—there’s no data or public information. Everything is hidden from our knowledge.”

Song Tang and Yi Ru contributed to this report.