In my last essay, I wrote about two fundamental principles of the circular economy: minimizing waste and keeping materials in circulation at the highest value for as long as possible. This week, I’ll wade into the waters of the third principle, regenerating nature.

The first two principles are usually discussed in reference to private sector activity because businesses are responsible for producing less waste and keeping their products and packaging recirculating. While these strategies require collective action, the private sector often holds the most powerful levers. Regeneration requires a more consistent mix of stakeholders: the private sector, academic institutions, nonprofits, policymakers and the public.

Regenerating nature means any activity that supports natural processes, allowing ecosystems and the services they provide to flourish. Every piece of our economy and society — from financial markets to human health to political stability — depends on thriving ecosystems. With the dual threats of biodiversity loss and climate change looming large, regenerating nature is an indispensable pillar of the circular economy.

Examples of nature regenerated include the Everglades and the work to restore marsh habitat there or Yellowstone National Park and the benefits the reintroduction of gray wolves has had on the greater regional system. Restoring nature can also benefit the private sector, by safeguarding jobs in tourism and other industries that rely directly on healthy ecosystems, such as forestry, farming and fisheries. Both the Everglades and Yellowstone National Park hold special meaning to me, as I’m sure many flourishing, natural spaces do for you. I turn my attention today, though, not to a successful story of regeneration but to an ecosystem in dire need of it: The Great Salt Lake.

Why so salty?

The Great Salt Lake was formed about 11,000 years ago, a shallow remnant of ancient Lake Bonneville. About 14,500 years ago, in one pivotal moment, this ice age lake breached a sandstone wall in Idaho, sending a massive volume of water northward. This flash flood, the biggest the world has seen, led to a 350-foot water-level drop in a matter of weeks.

Today, covering 1,600 square miles, the Great Salt Lake is famous for its salt content and is the largest natural lake west of the Mississippi River. Water flows in through the Bear, Ogden, Weber and Jordan rivers, as well as snow runoff and precipitation. The lake has no natural outlets — water leaves only through evaporation and withdrawals, meaning that sediment, minerals and pollutants carried into it stay put. As the water level fluctuates, the salinity of the lake changes, ranging from 5-27 percent over the past few decades (the ocean sits at a relatively stable 3 percent). There is a mind-boggling 4.5 billion tons of salt in the lake, and about 2 million tons are added through rivers every year.

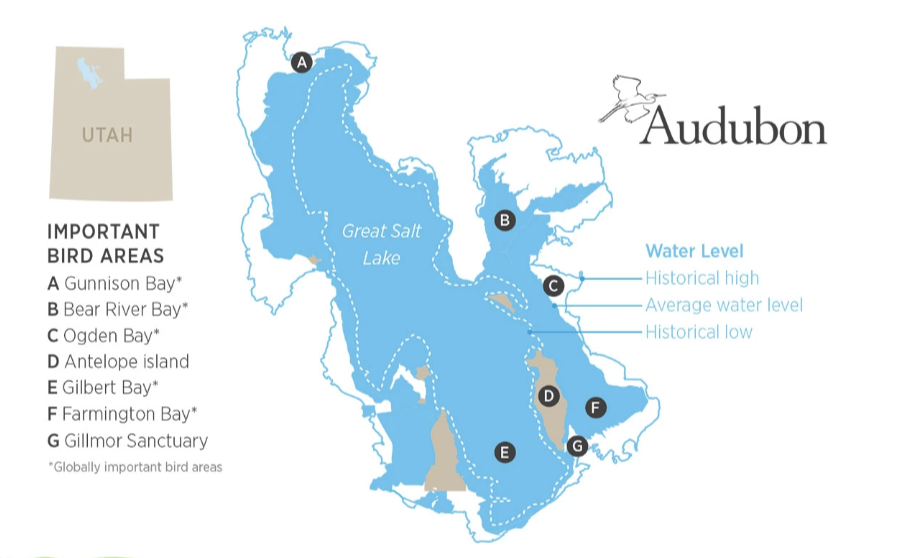

Why does this matter? This salinity makes for a unique ecosystem supporting an abundance of brine shrimp, algae, zooplankton, bacteria and insects. This combination of prey and the limited bodies of water in this arid landscape make the lake a vital ecosystem for migratory bird populations that rely on the lake for wintering habitat, migratory stopovers and as a site for breeding. The lake’s five major bays are all identified as globally Important Bird Areas by the Audubon Society.

From bad to worse

Over the past century, the ecological state of the Great Salt Lake has been affected by a number of factors, including water diversion, pollution and development. Across the state of Utah, water use is split among agricultural (82 percent), residential (10 percent) and industrial (8 percent). The diversion of tributary rivers has decreased the water level, exposing large swaths of the lakebed and increasing salinity levels. This, combined with the historic drought across the west exacerbated by climate change, has created an impending “ecological crisis.”

Chemical and nutrient runoff from agriculture, industry and urban development have led to an increase in algal blooms, depleting oxygen levels, threatening aquatic life and affecting the functioning of the entire ecosystem.

And the increasing exposure of dry lakebed presents an array of health and financial problems. Toxins such as mercury, arsenic and lead can become airborne and impact local air quality, putting the health of millions at risk. Economic projections estimate the financial cost of declining water levels in the lake at $25.4 billion to $32.6 billion over the next 20 years.

Without urgent action, the impacts to the ecosystem and surrounding populations have the potential to be catastrophic, following a similar trajectory to Lake Owens, a dried lake outside Los Angeles that gave this area the unenviable title of worst dust pollution in the U.S.

What has been proposed?

A number of strategies have been proposed to support the Great Salt Lake’s path to recovery, starting with restoring water levels as the highest priority. Reducing the amount of river water diverted for agricultural, urban and industrial use will ensure enough water flows into the lake to maintain its ecological health.

Regulating industrial and agricultural discharges; promoting more sustainable agricultural practices; and restoring wetlands around the lake can also improve water quality and minimize the risk of harmful algal blooms.

Raising awareness about the role the lake plays in the region’s ecology and culture and the threats it faces can help foster a greater sense of stewardship and promote conservation.

We cannot achieve a new, circular system without clear and intentional work from all to give nature the opportunity to regenerate.

Continued research and monitoring will help improve our understanding of the lake’s ecosystem and ensure conservation efforts are based on the best available science. In 2022, the Utah legislature passed a bill (HB 429) requiring the Department of Natural Resources to conduct an integrated water assessment of the lake by November 2026. While this is a crucial first step, given the urgency of the situation, the timeline needs to be accelerated.

These strategies will all play an important role, but the longevity and health of the lake demands a more urgent and specific plan. Scientists have estimated that without immediate action, the lake could dry up in as little as five years. Five years is a terrifyingly short period of time for an ecosystem and for Utah locals such as myself. What clear, concrete actions can be taken now?

The nitty-gritty

To get to the level of detail I craved, I dove into a recently released policy assessment report published by the Great Salt Lake Strike Team, a partnership of researchers and state agencies working to provide the science and data to answer thorny questions around the recovery of the lake. A few major opportunities stand out:

- Set a target water range for the lake. A science-based, ambitious water range target must be set by the state, in addition to a clear timeline. Scientists have already identified this target (optimal elevation range: 4,198-4,205 feet) — now policymakers must acknowledge and work towards it. Monitoring and evaluation should inform if and when that goal needs to be recalibrated.

- Implement agricultural optimization plans to improve efficiency and decrease water use for agriculture. This includes activities such as improvements to irrigation infrastructure, changes to on-farm soil, crop and water management and adoption of fallow programs. Support and funding for these activities will undoubtedly be one of the most critical pieces of the plan to save the lake.

- Years of above-average precipitation must be leveraged. These years (such as this one, with record-breaking snowpack in Utah) are the most important years for managing water and offer the opportunity to set more aggressive goals to achieve conservation success beyond initial projections.

- Invest in more research capacity. Resources and experts that enable the monitoring and modeling of water levels are essential to meet any set goals.

- Continue advancing specific policy analysis and recommendations. Providing clear, discrete actions allows policymakers to follow the science for every decision.

These actions provide a clearer path forward, but they’ll require urgent action from state leadership, researchers and all those who use water in the high desert. Businesses also have a major role to play in examining their current water footprints and adapting to our new reality.

We cannot achieve a new, circular system without clear and intentional work from all to give nature the opportunity to regenerate. Here in Utah, we have our work cut out for us.

[Interested in learning more about the circular economy? Subscribe to our free Circularity Weekly newsletter.]