Advertisement

Singapore’s well-established advantages, ranging from political and economic stability to developed infrastructure, will continue to give it an edge, but the country needs to be “nimble” to ward off rising competition for investments, experts say.

SINGAPORE: Surrounded by lawmakers and business leaders, United States President Joe Biden was all smiles as he signed into law what he called “a once-in-a-generation investment in America” on the morning of Aug 9, 2022.

A rare major foray into US industrial policy, the Chips and Science Act was a spending package that would devote US$52 billion to scientific research and American production of semiconductors.

“The future of the chip industry is going to be made in America,” the US President said in a speech before signing the landmark Bill, igniting cheers from the crowd of political leaders, union presidents and tech executives gathered at the South Lawn of the White House.

But beyond wooing investments back home to rebuild the US chip industry and create jobs, the new legislation is also an attempt to protect US national security.

America needs chips for key weapons systems like Javelin missiles, but the country now produces “zero per cent” of these sophisticated components that form the heart of almost every modern piece of machinery.

“China is trying to move ahead of us to manufacture these sophisticated chips … US must lead the world in the production of these advanced chips and this law will do exactly that,” said President Biden.

Alongside the multi-billion-dollar legislation, the US has announced a sweeping set of export controls targeted at China while latest proposed rules from the US Commerce Department are seeking to limit recipients of US funding from investing in “foreign countries of concern”.

The move has also spurred other governments in Europe and Asia that are home to major chip companies to introduce similar policies to maintain their own positions in the industry.

Such industrial policies borne out of geopolitical and economic rivalry combined with an ongoing overhaul of global corporate tax rules, are bad news for Singapore’s small and open economy, policymakers here have warned.

For decades, Singapore has attracted a steady flow of multinational companies to its shores to invest in sectors including electronics, pharmaceuticals and finance. But competition for these investments is set to stiffen, as greater economic nationalism and protectionism rear their ugly heads.

“While lip service is still paid to free trade and openness, protectionism is on the rise,” said Grant Thornton Singapore’s practice leader and head of tax David Sandison.

In his Budget speech earlier this year, Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong noted that as the US and other countries dole out huge subsidies to build up strategic industries, Singapore will not be able to outbid them.

The overhaul of global corporate tax rules aimed at combating base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) by large firms, also means reduced scope for Singapore to use tax incentives to attract new investments.

“Singapore will have to adapt quickly to these changes, to survive and prosper in a troubled world,” he said.

Experts believe that Singapore’s well-established advantages, ranging from political and economic stability to developed infrastructure, will continue to give it an edge.

But the country needs to be nimble in adapting its policies to ward off rising competition.

“While Singapore has other non-tax factors that already make it a compelling business hub location, it would still need to ensure that its incentive framework remains competitive … especially in areas such as innovation and ESG,” said Mr Andy Baik, partner and head of US tax desk at KPMG in Singapore.

GLOBAL COMPETITION, DOMESTIC COST ISSUES

Policymakers have long described foreign investments as a way to inject vibrancy into the economy.

Attracting multinational corporations to anchor their global or regional operations in Singapore can help to develop key industries and create jobs. They also generate spin-offs for local firms, which may start off as suppliers and sub-contractors to these global firms before growing into industry leaders.

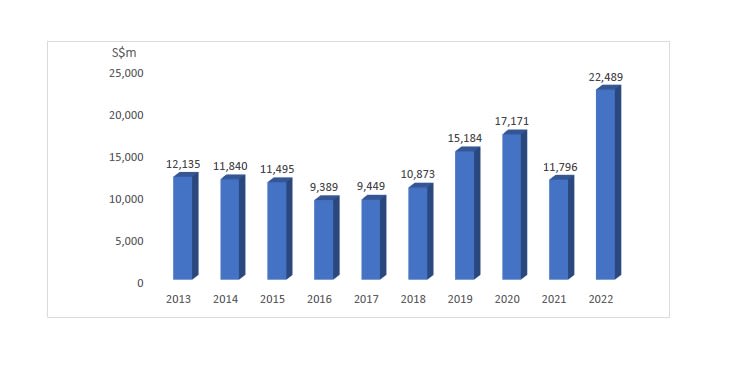

Last year, Singapore attracted a record S$22.5 billion (US$17 billion) in fixed asset investments, nearly doubling from the year before. In all, the projects secured are expected to create 17,113 new jobs when they are fully implemented in the next few years.

Attributing the record investment haul to an “exceptional inflow” of large manufacturing projects in the first half of 2022, the Economic Development Board (EDB) has said that it does not expect the same level of investments this year partly due to intensifying competition.

Apart from the US Chips and Science Act, the US Inflation Reduction Act is another incentive programme “that will compete for the same sorts of investments that Singapore would be interested in”, EDB chairman Beh Swan Gin told reporters at a press conference in February.

The US Inflation Reduction Act comprises billions of dollars of subsidies for the purchase of electric cars and other eco-friendly products that are made in America. This has rattled many European nations who fear that companies may choose to relocate or at least prioritise investment in the US.

In response, the European Commission has presented a Green Deal Industrial Plan with higher levels of state aid to help Europe compete as a manufacturing hub for clean tech products.

Then, there is BEPS 2.0 which is advocating a minimum effective tax rate of 15 per cent for multinational groups with annual group revenues of at least 750 million euros (US$818 million).

Currently, Singapore’s headline corporate tax rate is at 17 per cent but the effective tax rate of many businesses may be lower than that, or even the proposed global minimum, due to tax incentives given to those seen as beneficial to the country’s economic development.

Singapore has said it will implement a domestic top-up tax for these large multinational enterprises – about 1,800 of them currently meet the revenue threshold – from 2025.

Already, these firms are having concerns about how the new global tax rules will erode their tax savings in Singapore and mulling whether they should be looking at relocating or making new investments in other countries, said Mr Baik.

“Certainly, tax is just one of the factors in this evaluation process but recent global tax developments have undoubtedly elevated the tax benefits consideration among the factors.”

Meanwhile, the cost of doing business in Singapore has crept up the list of concerns for businesses.

Beyond the inflationary push in operating expenses such as electricity, firms are increasingly mindful of the cost of living here, said Dr Lei Hsien-Hsien, chief executive officer of The American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) in Singapore.

The Singapore International Chamber of Commerce (SICC) said global companies are most concerned about the elevated rental costs for residential and commercial premises.

The former, in particular, is “making living here much less viable for many expat executives and prohibitive for others”, and this impacts a company’s ability to relocate talent to Singapore.

While Singapore continues to stand out for having low risks of doing business, SICC said “there is no room for complacency” as its regional peers can now better manage risks than before.

“When combined with lower business costs, regional markets will remain attractive to investors based on their risk appetite and their specific business requirements,” the chamber said.

A separate survey, released this week by the European Chamber of Commerce Singapore, also showed that 69 per cent of companies are ready to relocate their staff out of Singapore if there is no relief from rising rental costs of residential and office spaces.

Mr Wong, who is also Finance Minister, has warned that multinational firms are “mobile and … have options” for their next investment projects. Already, firms are “making this clear” in consultation sessions with policymakers.

“Because of BEPS, they will no longer enjoy the same tax advantages in Singapore. Meanwhile, other countries in the region are cheaper, while their home countries are offering very generous incentive packages,” Mr Wong said in his Budget round-up speech on Feb 24.

“So they ask us: what else can Singapore offer to stay competitive?”

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

Singapore will have to tweak its policy toolkit – both in terms of how it structures its benefits and which areas to focus on – to remain top-of-mind among global investors, experts said.

While an array of grants is currently available for businesses, they can be enhanced “with flexibility to support a wider variety” of activities, such as capability building and investments in the environmental, social and governance (ESG) agenda, said Deloitte Singapore’s global investment and innovation incentives leader Yvaine Gan.

To ensure Singapore remains as a prime location for high-value investments, “customised” support should be rendered, especially for new growth areas like sustainability and space technology, she added.

This includes access to suitable land sites or ready-built facilities, as well as talent facilitation schemes for specialised skillsets that Singapore lacks currently.

Singapore may also have to eventually consider other forms of support such as subsidies, as BEPS 2.0 erodes the benefits of tax incentives. This could come in the form of taxable cash grants to help defray business spending, said Ms Liew Li Mei, international tax leader from Deloitte Singapore.

But with subsidies involving government spending regardless of whether the recipients are profitable, any move on this front will likely be gradual to weigh the economic costs and benefits, she noted.

That said, tax incentives “are by no means dead” given how about half a million companies here will be unaffected by BEPS 2.0, said Grant Thornton’s Mr Sandison.

The new global tax rulebook also allows for tax incentives if they are “based around real and substantial activities in the jurisdiction”, he added.

In this case, tax experts suggested qualified refundable tax credits as one consideration.

These are “tax incentives where the tax benefits may be converted to cash within four years”, and Singapore can target these credits at areas such as innovation and sustainability, said KPMG’s Mr Baik.

Another would be tax incentives based on business spending on payroll and fixed assets. These can, for example, take the form of “more generous investment allowances schemes” for businesses investing in construction, equipment, and other plant and machinery in Singapore, he suggested.

Experts said BEPS 2.0 presents an opportunity for Singapore to rejig its business incentives regime, but close attention will have to be paid to other jurisdictions for clues on implementation given the uncertainty surrounding the roll-out of complex new tax rules.

“What is inevitable … is that all countries are in for a number of years of edging forward by trial and error, if not total chaos, with no jurisdiction nailing it straight away,” said Mr Sandison.

Deloitte Singapore’s tax partner Loh Eng Kiat noted concerns from many multinationals about how a full and hasty implementation of BEPS 2.0 may result in responses from other countries that would further destabilise the global economy.

“Such feedback strengthens our belief that it is in the best interests of Singapore not to be the first mover in enacting the rules domestically,” he said.

Singapore’s current implementation timeline from 2025, which is a year after several jurisdictions, is “a strong signal that … Singapore will not simply jump on the bandwagon”. This will help subject businesses to “a lesser degree of road-testing”, added Mr Loh.

Being attractive to global investors also means the presence of a vibrant business ecosystem with local firms, as well as a competitive workforce.

Again, a bundle of initiatives targeting digitalisation and other enterprise capabilities, as well as skills upgrading, is available with additional support doled out at each year’s government budget.

Budget 2023, for example, extends and tops up several programmes like the National Productivity Fund and the Market Readiness Assistance scheme that helps local companies to venture abroad.

More can still be done, with Ms Gan suggesting the grant cap of S$100,000 per new market in the Market Readiness Assistance scheme to be raised to encourage more SMEs to internationalise.

Other schemes aimed at building local capabilities can also direct more attention to sustainability-related fields to strengthen development of expertise in this emerging area, she added.

“NEVER COMPETED SOLELY ON INCENTIVES”

Beyond incentives, experts believe that the appeal of Singapore as a top investment destination will continue to be burnished by well-established attributes ranging from developed infrastructure to strong rule of law.

Such attributes remain important considerations for businesses, said Deloitte’s Ms Liew, adding that Singapore “has never competed solely on incentives”.

Agreeing, AmCham’s Dr Lei noted that Singapore is still on the consideration list of companies, especially those looking to establish a presence in Asia for the first time.

“What makes Singapore more attractive than another country isn’t always the tangible incentives,” she said, citing a “welcoming” environment to do business and an “adaptable” workforce. Businesses also welcome the consultative approach taken by authorities for policy changes.

“Can we still attract new companies to come to Singapore? I think the answer is still yes,” said Dr Lei.

For the year ahead, a strong growth outlook for the region will help to support a “positive” investment climate, said S&P Global Market Intelligence’s Asia-Pacific chief economist Rajiv Biswas.

Within which, Singapore remains a “highly attractive” location, including for the chip industry. This is because global firms have become increasingly concerned about disruption risks and are reconfiguring their supply chains towards “manufacturing hubs with a high level of political and economic stability”.

Said Mr Biswas: “While the US and EU incentives will attract some new semiconductors manufacturing capacity, Singapore can also benefit from the reshaping of semiconductor supply chains due to its strong advantages of political and economic stability, as well as high quality power infrastructure.”

Last December, French semiconductor materials supplier Soitec announced a S$571 million investment to double the production capacity of its wafer fabrication plant in Singapore.

The investment – part of the firm’s EUR1.1 billion capital spending program announced in 2021 – will also double headcount at the Pasir Ris plant to more than 600 by 2026.

Singapore is “at the heart of (Soitec’s) long-term growth strategy”, a company spokesperson told CNA, citing factors such as a strategic location to key clients in the region, a favourable business climate and infrastructure, as well as the availability of highly-skilled talent.

While financial incentives are welcome, other factors “carry equal if not more weight in deciding where a new plant is located”, it said when asked for its view on incentives doled out by other countries.

“The semiconductor industry is extremely capital-intensive, and its supply chain complex and fragmented, so it is critical to be able to operate a semiconductor plant with high efficiency,” said the spokesperson.

“This can be more easily achieved when your upstream and downstream partners are located close by.”

Other Western chipmakers and related suppliers, such as Applied Materials and GlobalFoundries, have also ploughed on with their multi-million investments to build new plants here.

These investments are “testament to the strong partnership” that Singapore has built up with the industry players, said Singapore Semiconductor Industry Association’s executive director Ang Wee Seng.

Singapore “cannot compete on the basis of financial incentives alone”, which is why the government has introduced grants for research and development, updated transformation maps, and support for firms to tackle longer-term challenges such as being more sustainable, he added.

“We believe that these strategies will allow Singapore to continue to grow and develop the sector, to ensure we remain a critical node in the global semiconductor value chain amidst the intensified competition,” said Mr Ang.

Amid the heightened competition, EDB said it sees opportunities in high growth and high value-add sectors such as the digital economy and advanced manufacturing for electronics, healthcare and aerospace.

Healthtech start-up Doctor Anywhere, for one, said global investors remain drawn to Singapore for its well-established advantages of being a business and talent hub, as well as a gateway to Southeast Asia.

There are overseas venture capital funds that are currently looking to set up physical offices here, as they scout for new investments, said founder and CEO Lim Wai Mun.

That said, the country’s proven track record has to be complemented with the presence of thriving local firms that can “capture” the attention of investors. In this case, Mr Lim said government grants have been very useful for him and other local entrepreneurs in the initial days of starting out.

Doctor Anywhere started in 2017 when telemedicine was a foreign concept. But the COVID-19 pandemic changed that, fuelling the start-up’s exponential growth in six countries including Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia. It now has about 600 employees across the region.

Last December, it announced that it has raised an additional US$38.8 million in its Series C1 round led by Denmark life science investor Novo Holdings, with participation from existing investors including Singapore’s EDBI.

“Even if you have investors coming in, you will need something to catch that money. In this case, the government coming in to support the ecosystem with various grants and training has enabled the supply of (local firms) to catch these investments,” said Mr Lim.

“That is how that whole flywheel effect happens. As more money comes in, you have more resources to fund more ideas and that keeps the ecosystem going even further.”